Hello, I am Aarti Sarvaiya, a student of MK Bhavnagar University. This blog I have written as a response to the Thinking Activity, Which is a part of my academic Work. Which we get after each unit. In this blog, I will discuss Arundhati Roy's book 'The Ministry of Utmost Happiness'.

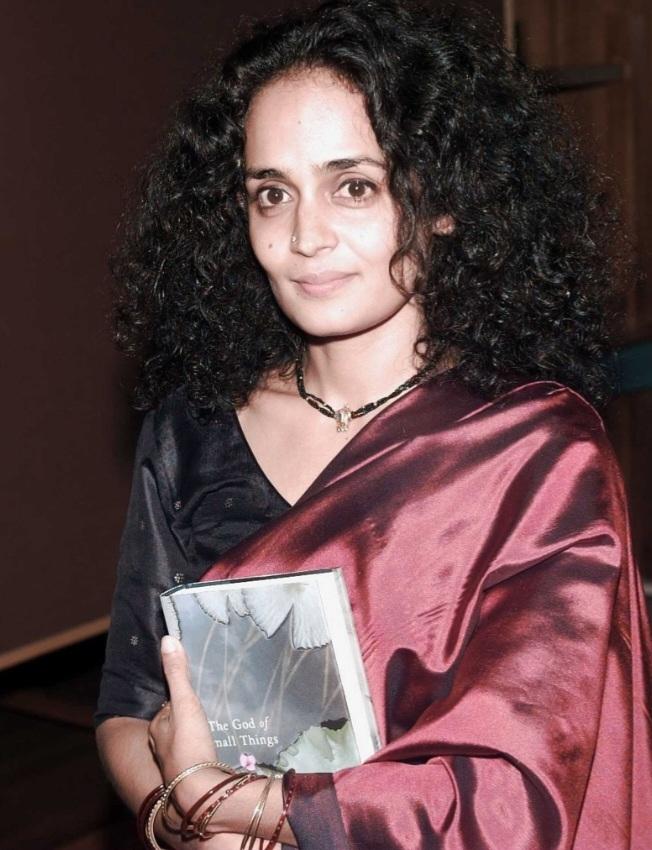

About Arundhati Roy

Full name of Arundhati Roy is Suzanna Arundhati Roy. She was born on 24 November 1961. She is an Indian author, essayist, and Political activist. She is best known for her novel The God of Small Things (1997)which won the Booker Prize for Fiction in 1997 and became the best-selling book by a non-expatriate Indian author. She is also involved in human rights and environmental causes. She also received many awards including the National Film Award for Best Screenplay (1988), Booker Prize (1997), Sydney Peace Prize (2004), Orwell Award (2004), Norman Mailer Prize (2011), etc.

Arundhati Roy also worked in television and movies. She wrote the screenplays for In Which Annie Gives It Those Ones (1989) and Electric Moon (1992), the film Bandit Queen by Shekhar Kapur. Roy won the National Film Award for Best Screenplay in 1988 for In Which Annie Gives It Those Ones. She also wrote novels, her best-known novel is, The God of Small Things, began writing in 1992, completing it in 1996. This is her first novel. Secondly, she wrote 'The Ministry of Utmost Happiness' in 2007.'The Ministry of Utmost Happiness' was nominated as a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award for fiction in January 2018. Watch this video to learn more about her.

About 'The Ministry of Utmost Happiness'.

The Ministry of Utmost Happiness is the second novel by Indian writer Arundhati Roy, published on 6 June 2017. The novel was originally written in English.it is a Fiction. The novel was published by Hamish Hamilton (UK & India) and Alfred A. Knopf (US). The novel is set in India and covers a wide range of India and some parts of Canada. it contains 449 pages.

The novel weaves together the stories of people navigating some of the darkest and most violent episodes of modern Indian history, from land reform that dispossessed poor farmers to the Bhopal disaster, the 2002 Godhra train burning, and the Kashmir insurgency. Roy's characters run the gamut of Indian society and include an intersex woman (hijra), a rebellious architect, and her landlord who is a supervisor in the intelligence service.

Questions based on This Novel:-

1) How are the intertextual references to other writers in the novel connected with the central theme of the novel? [also mention the epigraphs in English & Hindi]

Arundhati Roy's "The Ministry of Utmost Happiness" intricately weaves intertextual references to other writers throughout its narrative, serving as thematic anchors that deepen the reader's engagement with the central themes of the novel. Each section begins with an epigraph, a short quote from poets and writers who embody resilience, resistance, and the human spirit amidst adversity. These epigraphs not only set the tone for the respective sections but also establish a dialogue between Roy's narrative and the broader literary and socio-political context.

The first section opens with a quote from Nâzim Hikmet's poem "On the Matter of Romeo and Juliet," invoking themes of love and identity. Hikmet's words, "I mean, it's all a matter of your heart," resonate with Roy's exploration of the fluidity of identity and the interconnectedness of human experiences. Through playful language and references to cultural myths, Roy introduces her characters, imbuing them with complexity and depth from the outset.

Pablo Neruda's question, "In what language does the rain fall on tormented cities?" sets the stage for the second section, probing the nature of suffering and resilience. Roy draws parallels between Neruda's poetic inquiry and the political turmoil depicted in the novel, underscoring the universality of human struggles across geographical and cultural boundaries. "बारिश किस भाषा में गिरती है/ यातनाग्रस्त शहरों के ऊपर? - पाब्लो नेरुदा"

The third section begins with a quote from Agha Shahid Ali's Kashmiri poem, evoking themes of death and bureaucratic indifference. This epigraph foreshadows the portrayal of the oppressive political landscape in Kashmir and the characters' struggles against state-sanctioned violence. Through Shahid Ali's poignant verse, Roy sheds light on the human cost of conflict and the resilience of those caught in its midst. "मौत एक छरहरी नौकरशाह है, मैदानों से उड़कर आती हुई - आग़ा शाहिद अली"

Jean Genet's words, "Then, as she had already died four or five times, the apartment had remained available for a drama more serious than her own death," herald the fourth section, emphasizing the intensity of human drama and the complexity of existence. Genet's themes of death and redemption find echoes in Roy's narrative, as characters grapple with their own mortality and search for meaning amidst chaos and upheaval. "क्योंकि वह पहले चार या पाँच बार मर चुकी थी, अपार्टमेंट उसकी मृत्यु से भी ज़्यादा गंभीर किसी नाटक के लिए उपलब्ध था। - ज्याँ जेने"

James Baldwin's reflection on truth and disbelief introduces the fifth section, drawing parallels between racial prejudice in the USA and caste discrimination in India. Roy expands Baldwin's insights to critique societal prejudices and challenges dominant narratives of oppression, highlighting the interconnectedness of global struggles for justice and equality. "और वे मेरी बात पर सिर्फ़ इस वजह से यक़ीन नहीं करते थे की वे जानते थे कि मैंने जो कुछ कहा था वह सच था। - जेम्स बाल्डविन"

Finally, Nadezhda Mandelstam's reflection on the changing seasons as a journey encapsulates the overarching themes of resilience and hope that permeate the novel. Mandelstam's words serve as a testament to the indomitable human spirit, inspiring readers to persevere in the face of adversity and uncertainty. "फिर मौसमों में परिवर्तन हुआ। 'यह भी एक यात्रा है,' एम ने कहा, 'और इसे वे हमसे छीन नहीं सकते।' - नादेज्दा मान्देल्स्ताम"

In conclusion, the intertextual references to other writers in "The Ministry of Utmost Happiness" enrich the novel's thematic depth and resonance, providing a literary tapestry that reflects the complexities of human experience. Through these epigraphs, Roy engages in a dialogue with a diverse array of voices, amplifying their perspectives and insights to create a narrative that is at once universal and deeply rooted in the specificities of Indian history and culture.

2) What is the symbolic significance of Vulture and Gui Kyom (Dung Beetle) in the novel?

In "The Ministry of Utmost Happiness" by Arundhati Roy, the vulture and Gui Kyom (dung beetle) carry symbolic significance representing various themes and aspects of the narrative.

The vulture serves as a symbol of death, decay, and scavenging. In the novel, vultures are depicted as omnipresent creatures, often seen circling above scenes of violence, death, and destruction. Their presence underscores the pervasive atmosphere of loss and suffering in the story, particularly concerning the ongoing conflicts and political unrest in Kashmir. Additionally, vultures are symbolic of the opportunistic nature of power and the exploitation of marginalized communities, as they feed on the carcasses left behind by conflict and oppression.

On the other hand, Gui Kyom, or the dung beetle, symbolizes resilience, renewal, and the cyclical nature of life. In Indian mythology and culture, the dung beetle is often associated with rebirth and transformation, as it rolls dung into balls to nourish its offspring. In the context of the novel, Gui Kyom represents the capacity for regeneration and hope amidst adversity. Despite the bleakness of the situations depicted in the narrative, the presence of Gui Kyom suggests that life continues to persist and adapt, even in the face of seemingly insurmountable challenges.

Furthermore, the juxtaposition of the vulture and Gui Kyom highlights the dualities and contradictions inherent in the human experience. While the vulture symbolizes death and decay, Gui Kyom symbolizes renewal and growth. Together, they reflect the complexities of life in a world marked by violence, and suffering, but also resilience and the possibility of transformation.

In conclusion, the symbolic significance of the vulture and Gui Kyom in "The Ministry of Utmost Happiness" underscores the novel's exploration of themes such as death, resilience, and the cyclical nature of life. Through these symbols, Arundhati Roy crafts a richly layered narrative that invites readers to contemplate the complexities of existence amidst tumultuous times.

3) Instead of privileging the center stage, "The Ministry of the Utmost Happiness" shifts the spotlight to the back alleys and hidden corners, granting agency to those typically relegated to the sidelines. Analyze how Roy's decision to center the periphery enriches our understanding of social, political, and existential realities often ignored by mainstream narratives.

Arundhati Roy's "The Ministry of Utmost Happiness" is a narrative marvel that resists the conventional tendency of centering mainstream characters and narratives. Instead, it boldly shifts the spotlight to the back alleys and hidden corners, granting agency to those typically relegated to the sidelines. This narrative strategy is not just a stylistic choice; it's a profound political and existential statement that enriches our understanding of social, political, and existential realities often overlooked by mainstream narratives.

At the heart of Roy's narrative lies a profound commitment to amplifying marginalized voices. Through her characters, she brings to life the stories of individuals whose voices are often silenced or ignored in mainstream discourse. From Anjum, a transgender woman navigating the complexities of identity and belonging, to Musa, a Kashmiri freedom fighter grappling with the trauma of conflict, Roy gives voice to those living on the margins of society. By centering their experiences, struggles, and triumphs, Roy challenges readers to confront the lived realities of individuals facing discrimination, oppression, and marginalization based on factors such as gender, caste, religion, and ethnicity.

Through vivid descriptions of life in the periphery, Roy exposes the pervasive social injustice and inequality that exist within society. She paints a stark picture of the harsh realities faced by marginalized communities, including the poor, the LGBTQ+ community, and religious minorities. Through Anjum's journey, for example, readers confront the challenges of navigating a world that refuses to acknowledge her identity. Similarly, through Tilo's encounters with the victims of state violence in Kashmir, readers are confronted with the human cost of political decisions and the enduring struggles for autonomy, self-determination, and social justice.

Roy's narrative also delves deep into the political landscapes often overshadowed by dominant narratives. Through Musa's story and the backdrop of the Kashmir conflict, Roy sheds light on the complexities of regional conflicts, state violence, and political upheaval. She exposes the human cost of political decisions and the enduring struggles for autonomy, self-determination, and social justice. By centering the periphery, Roy offers readers a window into the lived experiences of those directly affected by political decisions and conflicts, challenging them to confront the consequences of their own complicity or indifference.

Moreover, Roy's nuanced character development humanizes individuals often reduced to stereotypes or caricatures in mainstream narratives. Through her characters' multifaceted identities, relationships, and motivations, Roy challenges readers to move beyond simplistic dichotomies of good and evil, victim and oppressor. Instead, she invites readers to recognize the inherent humanity and dignity of all individuals, regardless of their social status, background, or beliefs. By centering the periphery, Roy offers readers an opportunity to see the world through the eyes of those whose stories are often overlooked or marginalized, fostering empathy and understanding.

By centering the periphery, Roy also offers alternative perspectives and counter-narratives that challenge dominant discourses and disrupt entrenched power dynamics. Through her characters' voices, she invites readers to reconsider their preconceptions and assumptions about society, politics, and human nature. She challenges them to confront the complexities and contradictions of contemporary society and to envision more inclusive and equitable futures. In doing so, Roy not only enriches our understanding of social, political, and existential realities but also inspires readers to imagine and strive for a world where all voices are heard, valued, and respected.

In conclusion, Arundhati Roy's decision to center the periphery in "The Ministry of Utmost Happiness" is a bold and transformative narrative choice that challenges readers to confront the complexities of contemporary society. Through her vivid characters, richly drawn settings, and powerful storytelling, Roy amplifies marginalized voices, exposes social injustice and inequality, explores political landscapes, humanizes complex characters, and offers alternative perspectives. In doing so, she invites readers to reconsider their understanding of the world and to imagine new possibilities for collective action and social change.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment